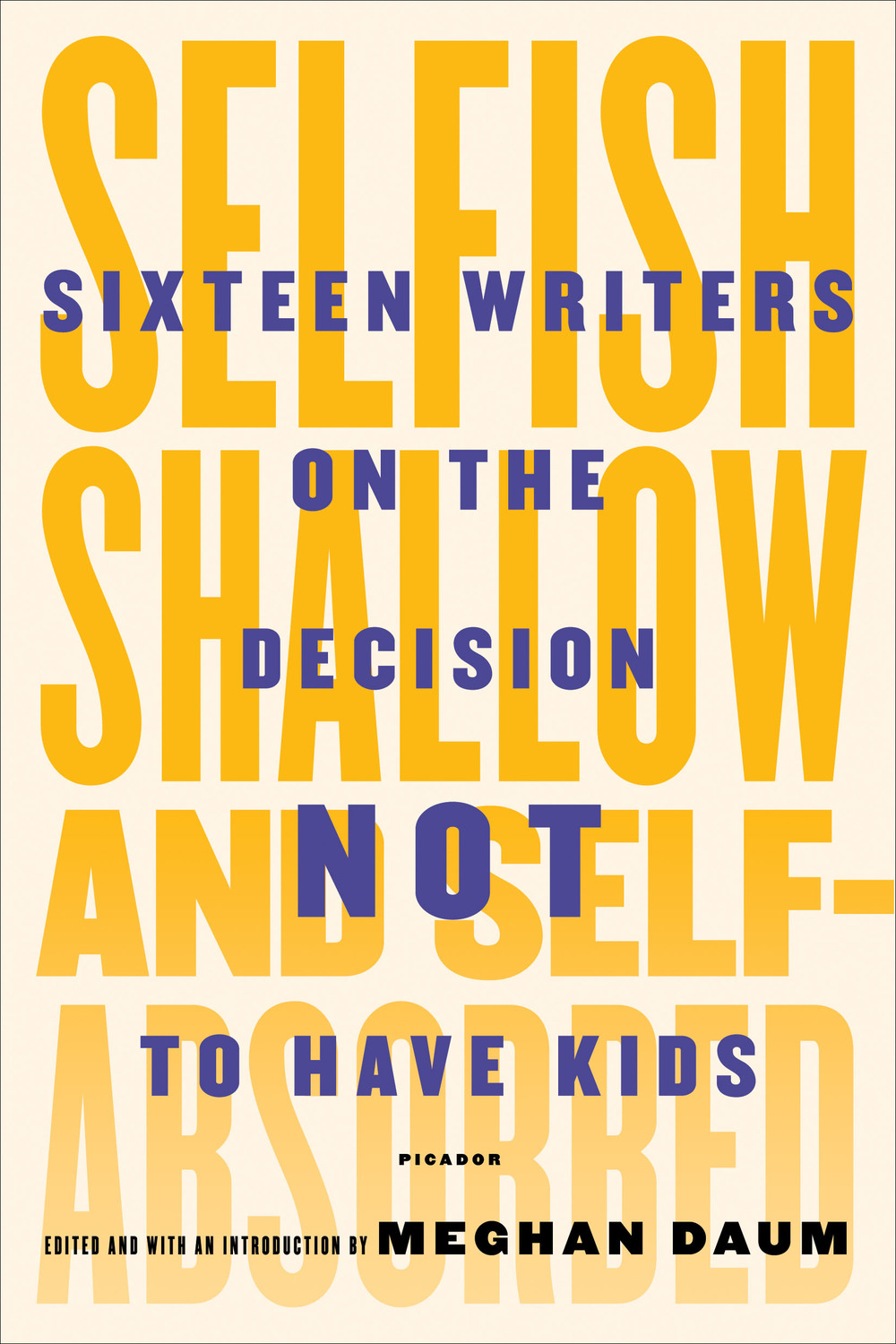

As someone who has been tracking the childfree choice since the late 1990s, when new books on this topic come out I read them with great interest. One of the latest is writer Meghan Daum’s Selfish, Shallow and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision NOT to have Kids. Meghan sent me an advance copy of this book of essays by 16 writers about how they came to this decision in their lives.

Her introduction is smart. She suspects the “majority of people who have kids are driven by any of just a handful of reasons, most of them connected to old-fashioned biological imperative.” Indeed. The AKA here is pronatalism, and how our social and cultural conditioning drives the creation of desire for parenthood in our society.

Daum writes, “It’s time to stop mistaking self-knowledge for self-absorption – and realize that nobody has a monopoly on selfishness.” I applaud how she seems to be after abolishing the pronatalist myth that those with no children are selfish and lead a selfish life. Despite what has been driven into our cultural hardware for generations, this is far from the truth. So is the myth that somehow if we don’t want a child there is something wrong with us. Like Jeanne Safer, who writes how she “didn’t really want to have a baby; she wanted to want to have a baby.”

The essays run from the deeply personal, to sociological, social and cultural discussion. Laura Kipnis wisely writes about how “maternal instinct” exists as social convention, not as “eternal” condition, and that it’s an “invented concept” that started at a certain point in history (she contends circa the Industrial Revolution, but I would disagree – it came long before that). She gets that what we call “biological instinct is a historical artifact – a culturally specific development, not a fact of nature.”

With years of talking to men and women in the midst of the parenthood decision, I can say a good deal of women with no children may relate to Kate Christensen. She is glad she does not have kids, but there was a time when she “wanted them more than anything.” However, when she thought she was pregnant and once that was over, she felt like she had been “saved from losing herself.”

And unlike other books on those who opt out of parenthood (OK with the exception of Families of Two ;)) we hear straight up from some guys. Take Paul Lisicky who speaks to how it wasn’t that he wanted to be a father as much as what not being one allowed him to be – and not be – how he did not have to restrict his “behaviors of some role.”

Other essays delve into how the writers understand and articulate their ambivalence, and what about them and their lives tipped the scale to “no.” Still others recount how situational factors ultimately landed them at “no.” Like Michelle Huneven, who reflects how, by the time she became “more able” and “even somewhat willing” to be a parent, and by the time she met a man who might be a wonderful father, it was just too late to “get that particular package.”

Other essays delve into how the writers understand and articulate their ambivalence, and what about them and their lives tipped the scale to “no.” Still others recount how situational factors ultimately landed them at “no.” Like Michelle Huneven, who reflects how, by the time she became “more able” and “even somewhat willing” to be a parent, and by the time she met a man who might be a wonderful father, it was just too late to “get that particular package.”

Still others like Geoff Dyer stumble “onto or into” the hearts of the matter. He gets into his truths of desire – specifically, his lack of desire for the parenthood experience. He writes how he has yet to hear a convincing argument why he should spend hours and years doing something he just does not want to do.

The paths are varied indeed. But one thing sticks out- that ending up with no kids, whether by circumstance, ambivalence, or life taking a certain course, ultimately other things were more important to these writers than the parenthood experience. Understanding what was more important will make you “get” these nonparent writers.

These honest and diverse essays add to other collections of essays written by those who have chosen to follow their own paths, and go against the grain of a pronatalist society. Daum’s collection joins Henriette Mantel’s No Kidding: Women Writers on Bypassing Parenthood and Aralyn Hughes’ Kid Me Not, which includes essays from women (she knows) from the 60s who are now in their 60s.

Beyond writers and boomers, the truth is, so many different kinds of people have their story about deciding to have no children. They are your servers in restaurants, your child care workers, your grocers, your teachers, your accountants, and the list goes on. They are from all walks in life – all occupations and lifestyles. May the next book in this nonparent essay genre expand the conversation to the larger reality – and present ever so clearly that we may remain in the minority – but we are everywhere.

Those who have landed on nonparenthood will understand how each person in this book landed at their choice in their own way. Daum’s book will help those in the midst of ambivalence to drill deeper into their own story. Parents and would-be parents who read this book will better understand how each person has their own road to making one of the most important decision of their lives.

I’d like to eventually get around to reading this book. I’ve also been able to read two chapters of the Baby Matrix, which I really liked. I don’t know whether I’ll have a kid or not (no one really does I guess), but this gives me ammunition for whenever some patronizing jackass who says a CFer will change their mind about parenthood. That really bugs me, this is an irreversible, extremely profound decision and strangers just lightly tell people “you’ll change your mind” almost to bring themselves satisfaction that everyone will do this one thing. It drives me mad. I can say, from what little I’ve read from your book, that I have less anxiety about the subject. If I choose to be CF, I think I’d be more confident in my decision, and less self-conscious about it.

Hi remaininlight-Thanks for writing~Meghan is a lovely essay writer in her own right, and has done a nice job at putting together a collection that shows the many, many ways people arrive at the choice to say no to parenthood. The “change your mind” messaging stems from the pronatalist belief that we are all supposed to want to have children. The reality is, as you may have read in The Baby Matrix already, that there is no real evidence to support the notion that we are biologically wired for the desire to want children. Understanding pronatalism and its generations of influence help us understand and see through truths and myths behind powerful social and social cultural conditioning around such an important decision in our lives!