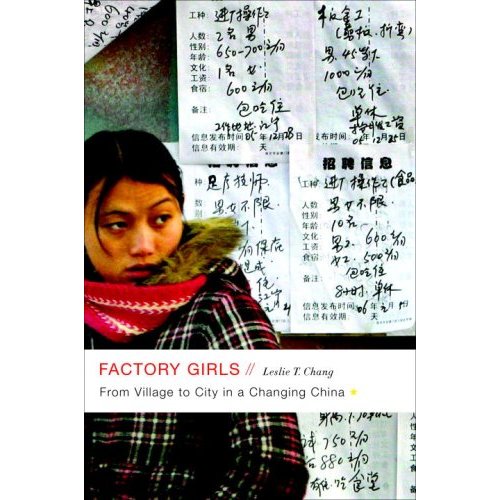

I recently had the pleasure of corresponding with a lovely Chinese woman named Zhang Jingjing about the book, Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China by Leslie Chang. It tells untold stories about the lives of the migrant factory population in China. I asked if Zhang Jingjing would be willing to summarize her experience of the book, and she graciously agreed. Here it is:

Zhang Jingjing on Factory Girls

As a girl who was born and grew up in a small village in the central part of China, I found Leslie Chang’s book, Factory Girls very interesting and touching. Chang describes a society struggling and thriving between the past and the present, with contradictory stories and phenomenons coexisting in the lives of two female migrant workers and her own family history. In reading Factory Girls, I felt how lucky and grateful I am to have been able to continue my studies while most other girls in my village went to work far away. I recalled some of the stories they told me, and how much they had changed when I saw them during the Chinese New Year festival, the only time they came back. I really enjoyed how this book mirrors what I learned personally from these girls.

Chang writes, “In traditional Chinese society, maintaining harmony with others was the key to living in the world. The moral compass was not necessarily right or wrong; it was your relationship with the people around you. And it took all your strength to break free from that.” When I read this along with other parts of this book, I choked back my tears. I was touched by her real understanding and compassion about the burden of being born Chinese. Chang, who was raised in America by immigrant parents, writes without judgement, which in my experience is rare for a foreigner.

The book is comprised of two parts – the city and the village. Each part has several stories through which readers experience the lives of migrant workers from village to city. Together, the parts create a silhouette of the industrialization and urbanization of contemporary Chinese society.

I like the chapter “To Die Poor is a Sin” quite a lot. I was impressed and touched by the determination and resourcefulness of the young woman in it. And as a Chinese woman of this generation, I can see the opportunities brought by development, and understand how lucky we are to enjoy so much more freedom with financial independence.

I was also moved by Chang’s family history and her personal thoughts on Chinese identity and the future of China. As she writes:

“China to them is not a political system or a group of leaders, but something bigger that they carry inside themselves, the memory of a place that no longer exists in the world. China calls them home – with the weight of its tradition, the richness of its language, with its five thousand years of history that sometimes seems to be one repeating cycle of tragedy and suffering. The pull of China is strong, which is why I resisted it for so long.”

“Perhaps China during the twentieth century had to go so terribly wrong so that people could start over, this time pursuing their individual courses and casting aside the weight of family, history, and the nation.”

Overall, I appreciate Chang’s efforts to tell our stories. I hope to see more books about us – Chinese women.

Thank you, Zhang Jingjing!

~In her own words about herself: “Zhang Jingjing is 100% made in China, has lived in France and Algeria, and is now back in China. She works for a NGO, has a huge curiosity about other cultures and is eager to travel the world.”