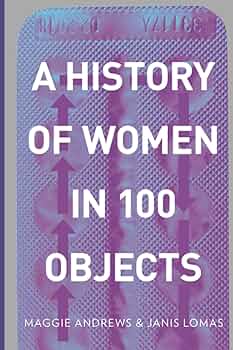

Review by Nicole Louie

A History of Women in 100 Objects starts with a disclaimer:

“Women’s history is multifarious, women’s experiences infinitely varied, too wide-ranging to be summarized by 100 objects. The objects we have included provide a starting point for exploring and discussing women’s past. They provide a sense of the rich heritage of women, stories of how women were encouraged to conform to ideas of femininity and how feminist forebears challenged any such pressures; the objects are indications of women’s oppression, heroism, ingenuity, skill and expertise.”

With the understanding that the authors set themselves the goal of telling one history of women, not the history of women, I delved into an encyclopedic journey covering many fields. Thanks to Maggie Andrews and Janis Lomas’s seamlessly combined wealth of trivia and photography, all eight parts of this book proved worth reading. The visual and textual samples about each object strike a balance between informative and engaging – they are long enough to inform the origin and importance of each selected piece but not too long to come across as a sluggish History lecture.

The further I read, the clearer it became how much thought also went into the placement of each object in the overall narration arc:

“Some of the objects could have been placed in a different section; the electric refrigerator, which was invented by New Jersey housewife Florence Parpart in 1914, could have come under “Wives and Homemakers”, but it’s included in the section on “Science, Technology and Medicine” as a reminder that domestic terminology is not something that is invented for women but something that women have taken a role in inventing themselves.”

Part I, “The Body, Motherhood, and Sexuality,” impressed me the most with its broad scope that features everything from factory-made disposable sanitary towels of the late 1800s (that meant the women who could afford the packets of white absorbent wool would stop using grass, leaves, rabbit skin and cheesecloth as reusable pads to contain their menstruation), to early 20th-century medical vibrators advertised as capable of removing wrinkles and curing nervous headaches, and the first apparatus for obstetric analgesia administered through a face mask to women in labor from the 1950s onwards.

Part II, “Wives and Homemakers,” showcases unsettling objects such as the scold’s bridle, “a heavy iron frame placed over the woman’s head and worn as a collar, with a plate fixed to the front projected into her mouth and immobilizing her tongue, leaving her unable to drink, eat or talk.” The use of this device from the 1500s punished for “women who exercised unruly speech” was finally removed from the British penal code in 1967. There’s also a photo of the report of a wife sale that illustrates the practice of trading wives by advertising them in newspapers when divorce laws didn’t exist or it was necessary to petition the parliament to dissolve a marriage in the 1800s and 1900s Britain.

Skimming through the corsets, veils and church hats of the “Costumes and Fashion” chapters and moving to “Transportation and Travel”, readers learn about the early days of ladies’ carriages in trains as a measure to keep them safe from sexual harassment and early critics opposing to it concerned “that women’s bodies were not designed to go at 50 miles an hour as uteruses would fly out of their bodies as they were accelerated to that speed.”

The following sections on “Technology”, “Employment”, “Creativity”, and “Women’s Place in the Public World”, introduce Joan of Arc’s Ring (1400s, France), the first policewomen’s armlet (1915, Britain), Billie Holiday’s Strange Fruit jazz and soul music album that gave a voice to black women’s experience (1939, U.S.), the 1000 lira banknote carrying the image of the renowned educator Maria Montessori (1990, Italy) among many other striking objects.

At first sight, in all its height, weight and numerous vibrant images, A History of Women in 100 Objects resembles a coffee table book that risks never being opened. But if you open it, you’ll realize it’s more of a machine with the power to teletransport its readers to one of the best history exhibitions ever created about women. If you see it, be sure to pick it up.

********************

Thank you, Nicole!

Nicole Louie is a writer and translator based in Ireland. Her essays have appeared in Oh Reader magazine, The Walrus and The Guardian. You can find her on Twitter and Instagram: @bynicolelouie. Others Like Me: The Lives of Women Without Children is her first book.