Review by Nicole Louie

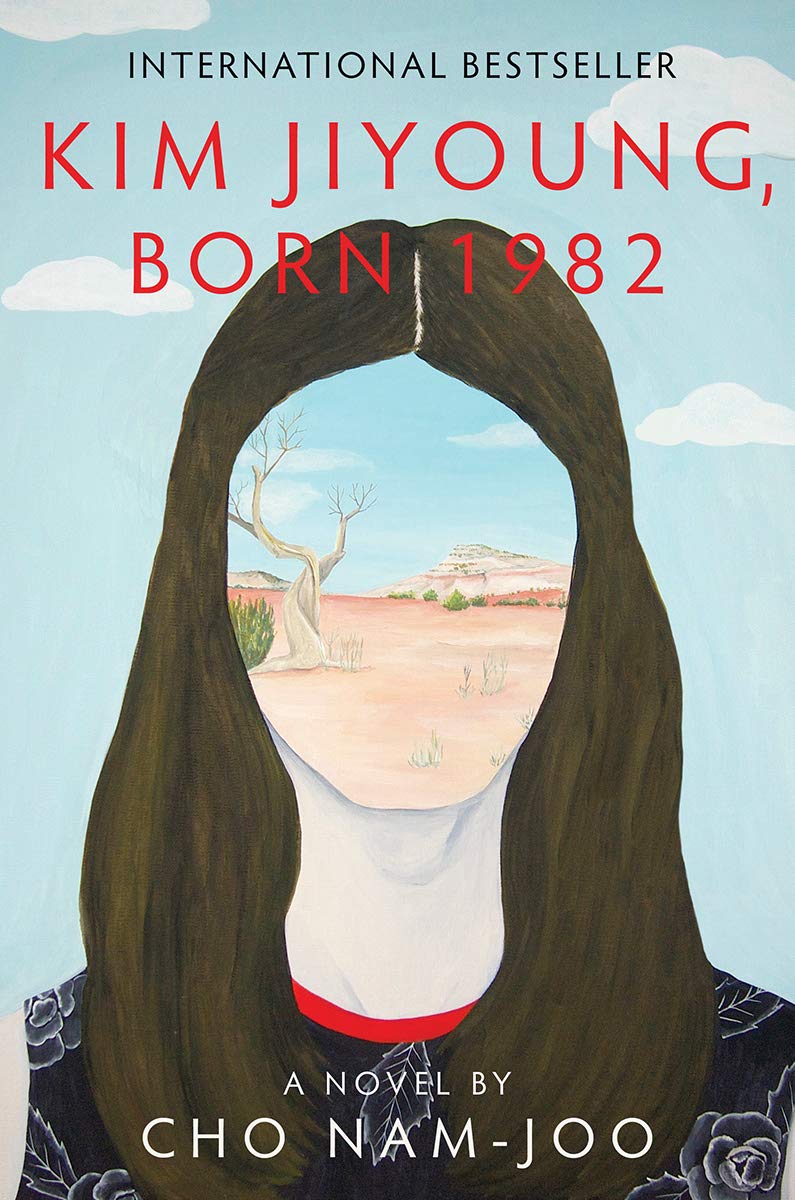

Originally published in Korean in 2016 and translated into English in 2020, the cover of the book, Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 immediately intrigued me. It has a woman’s head with no facial features and inside it only a desert-like landscape. The back matter teases with:

“Kim Jiyoung has started acting out.”

“Kim Jiyoung is her own woman.”

“Kim Jiyoung is insane.”

“Kim Jiyoung is sent by her husband to a psychiatrist.”

I brought the faceless woman home and delved into this book to find out why she had started “acting out.”

Kim Jiyoung is a 33-year-old Korean woman who lives in Seoul with her husband and newborn daughter. Her parents and in-laws live elsewhere, and her husband works until midnight and on weekends. After giving up her career for a life of domesticity, Kim Jiyoung has become the sole carer of her little girl. No matter how much she does, there’s always more to be done. And no matter how hard she tries, she feels her existence is neither satisfactory nor fair.

In a society that treats motherhood and martyrdom as the same thing, Kim Jiyoung has no one to talk to about how overwhelmed and lost she feels. The accumulation of her repressed thoughts and emotions leads to her breakdown, which manifests in the bizarre channeling of other women in her life, both dead and alive. She starts to talk like them, behave like them, even know things that only they know. But Kim Jiyoung doesn’t see that she is dipping into a kind of psychosis. Her husband doesn’t understand.

It’s easy to think it all started on page 122, in the passage where her husband suggests:

“There is one way to stop my parents’ nagging for good.”

“What?”

“Let’s just have a kid. If we are going to have one eventually anyway, why not avoid the lectures by just having one? We’re not getting any younger.”

But the root cause of her wounds goes back many years: her mother wanted a boy, her school enforced a strict dress code for the girls but not for the boys, her father blamed her when she was stalked by a classmate, she was called “someone else’s chewed gum” after having dated a colleague, she worked harder than everybody else but didn’t get promoted, she got married because she was told there was no reason to wait. Then she did what her husband wanted—she got pregnant to stop her in-laws from bullying her into becoming a mother.

As the story unfolds, we see that Kim Jiyoung’s trajectory is a personal tale of universal impositions many women worldwide face but with a particular focus on Korean women. In just over 160 pages, the well-thought-out structure has one section for each phase of Kim Jiyoung’s life: childhood, adolescence, early adulthood and marriage. It also illustrates a myriad of disturbing Korean female experiences with a unique combination of the fictional story interspersed with facts and data.

By citing statistics on education, marriage, abortion and workplace conditions, Cho Nam-Joo turns the discrimination suffered by women in various spheres into a public debate that can no longer be ignored. Here’s one example:

“In 2005, the year Kim Jiyoung graduated from college, a survey by a job search website found that only 29.6% of new employees at 100 companies were women, and it was even mentioned as a big improvement. Another survey concluded that among managers of fifty large corporations, 44% chose that they ‘would rather hire male to female candidates with equivalent qualifications,’ and none chose ‘would hire women over men.’”

Another data point she shares:

“According to 2014 data, women working in Korea earn only 63% of what men earn. Korea was also ranked as the worst country in which to be a working woman, receiving the lowest scores among the nations surveyed on the glass-ceiling index by the British magazine The Economist.”

Although the inclusion of dates and statistics felt a bit dry at first, I came to appreciate the author’s dedication and intention to provide her readers with a broader picture of gender inequality in her country. This effective way of interspersing social commentary with relatable anecdotes about a female protagonist turned the book into a symbol of the feminist movement in South Korea and catapulted it into a bestseller that has sold multi-million copies in eighteen languages.

Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 taught me a lot about misogyny, mental health and misdiagnoses in women. Kim Jiyoung’s life and breaking point in her early thirties not only gives readers a look into the Korean woman’s experience but also the experiences of women around the world.

***********************

Thank you, Nicole!

Nicole Louie is a writer, translator, and content curator based in Ireland. She is dedicated to finding and sharing the stories of amazing women without children both online and in her upcoming non-fiction book on childlessness. She can be found on Twitter and on Instagram: @bynicolelouie.